How (not) to access V8 memory from a Node.js C++ addon's worker thread

When we create C++ addons for Node.js, we have two strategies - synchronous or asynchronous processing. A synchronous C++ addon does it’s number crunching in the thread that Node.js’s event loop executes in. This, unfortunately, blocks all JavaScript execution until the C++ addon completes it’s work and returns control back to JavaScript. In asynchronous addons, we can execute the heavy lifting in a worker thread. This allows the initial call into the addon to return quickly to JavaScript - freeing up the Node.js event loop to continue it’s business. An asynchronous addon will invoke a JavaScript callback function when it has completed (or at least whenever it has something to return). If you are unfamiliar with asynchronous callbacks - check out two of my previous blog posts on the subject:

- Building an Asynchronous C++ Addon for Node.js using Nan

- C++ processing from Node.js - Part 4 - Asynchronous addons

Both of those posts (and pretty much anything else you read on the web about async addons) make the following assertion - either implicitly or explicitly:

you can’t access V8 (JavaScript) memory outside the event-loop’s thread.

This essentially means if you want the asynchronous part of your addon to be able to (1) access input data sent from JavaScript and/or (2) return data to JavaScript then you need to create copies of the input/output data. The mechanics work like this:

For situations where input data and output data is relatively small, this poses absolutely no issue - and I’d argue these are probably the most common cases. However - what if your async addon is going to do a lot of computation over a large input? What if it generates a huge amount of data? Note that in the figure above - copying input and output data is being done in the event loop - meaning if it takes a long time, we’re blocking the event loop (which we hate doing!).

So we have two problems:

- Copying data might be a waste of memory

- Copying data might take long, which ties up the Node.js event loop.

Ideally, we’d prefer a way to do this:

As mentioned above - this is something that the official Node.js and V8 documentation both specifically say we can’t do… however I think it’s instructive to see why (and documentation covering the “why” is hard to come by!). The remainder of this post is about how I went about proving to myself it wouldn’t work, and the ways I’d recommend mitigating the problem of copying within the event loop. Warning: most of this post contains anti-patterns for asynchronous addons with Node.js. I’m attempting to illustrate the details of why we must work with libuv and always access V8 data from the event loop - as is outlined in the posts I linked to above.

Handles - Local and Persistent

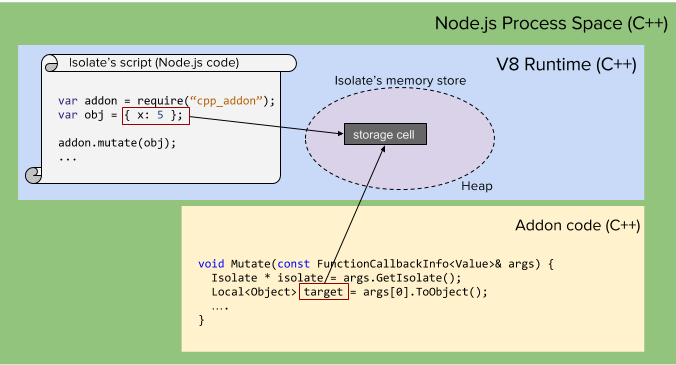

How does C++ access JavaScript data in the first place? It’s all explained in the V8 Embedder Guide - but I’ll breifly describe it here. When your Node.js JavaScript code is executing and allocating variables, it’s doing so within the V8 JavaScript engine. V8 allocates JavaScript variables within it’s own address space inside what we’ll call “storage cells”. When JavaScript calls into a C++ addon, the C++ code may obtain references to these storage cells by creating handles using the V8 API.

The most common handle type is Local - meaning it’s scope is tied specifically to the current handle scope. The scope of a handle is critical, as V8 is charged with implementing garbage collection - and to do this it must keep track of how many references point to given storage cells. These references are normally within JavaScript, but the handles in our C++ addons must be kept track of too.

The most basic form of accessing pre-existing JavaScript variables occurs when we access arguments that have been passed into our C++ addon’s when a method is invoked from JavaScript:

As you can see from the diagram, the Local<Object> handle we create (target) will allow us to access V8 storage cells. Local handles only remain valid while the HandleScope object active when they are created is in scope. The V8 Embedder’s Guide is once again the primary place to learn about HandleScope objects - however put simply, they are containers for handles. At a given time, only one HandleScope is active within V8 (or more specifically, a V8 Isolate). Where’s the HandleScope in the above example? Good question!

It turns out that Node.js creates a HandleScope right before it calls our addon on the JavaScript code’s behalf. This HandleScope is destroyed when the C++ addon function returns. Thus, any Local handle created inside our addon’s function only survives until that function returns - meaning Local handles can never be accessed in worker threads when dealing with async addons - the worker threads clearly outlive the initial addon function call!

Are Persistent handles the answer?

Maybe! As the name implies, Persistent handles are not automatically destroyed using HandleScopes - they can hang around indefinitely. Once you’ve created a persistent handle in your C++ code, V8 will honor that reference (and make sure you can still access the storage cells it points to) until you explicitly release it (you do this by calling the handle’s Reset method). At first glance, this appears to be precisely the tool that would allow a long-lived C++ worker thread to access V8 data.

As a first experiment, lets maintain a reference to a JavaScript variable across C++ function calls by setting up a simple (non-threaded) example. Let’s build a quick addon that allows JavaScript to pass in an object that the C++ hangs on to. Subsequent calls to the addon will mutate the JavaScript object originally passed into it - and we’ll see these changes in JavaScript after the C++ returns.

Note: All of the source code for this post can be found here. To follow along and run all the examples:

> git clone https://github.com/freezer333/node-v8-workers.git

#include <node.h>

using namespace v8;

// Stays in scope the entire time the addon is loaded.

Persistent<Object> persist;

void Mutate(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

Isolate * isolate = args.GetIsolate();

Local<Object> target = Local<Object>::New(isolate, persist);

Local<String> key = String::NewFromUtf8(isolate, "x");

// pull the current value of prop x out of the object

double current = target->ToObject()->Get(key)->NumberValue();

// increment prop x by 42

target->Set(key, Number::New(isolate, current + 42));

}

void Setup(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

Isolate * isolate = args.GetIsolate();

// Save a persistent handle to this object for later use in Mutate

persist.Reset(isolate, args[0]->ToObject());

}

void init(Local<Object> exports) {

NODE_SET_METHOD(exports, "setup", Setup);

NODE_SET_METHOD(exports, "mutate", Mutate);

}

NODE_MODULE(mutate, init)

If you are unfamiliar with building addons, a tutorial about the build tool (node-gyp) and the details of how to set it up can be found here.

Notice the two functions exposed by the addon. The first, Setup, creates a (global) Persistent handle to the object passed in from JavaScript. This is a pretty dubious use of global variables within an addon - it’s probably a bad idea for non-trivial stuff - but this is just for demonstration. The point is that Persistent<Object> target’s scope is not tied to Setup.

The second function exposed by the addon is Mutate, and it simply adds 42 to target’s only property - x. Now let’s look at the calling Node.js program.

const addon = require('./build/Release/mutate');

var obj = { x: 0 };

// save the target JS object in the addon

addon.setup(obj);

console.log(obj); // should print 0

addon.mutate();

console.log(obj); // should print 42

addon.mutate();

console.log(obj); // should print 84

When we run this program we’ll see obj.x is initially 0, then 42, and then 84 when printed out. Living proof we can hang on to V8 within our addon across invocations… we’re on to something!

> node mutate.js

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 42 }

{ x: 84 }

Bring on the worker threads!

Let’s simulate a use case where a worker thread spends a long time modifying data iteratively. We’ll modify the addon from above such that instead of needing JavaScript to call Mutate, it repeatedly changes target’s x value every 500ms in a worker thread.

#include <node.h>

#include <chrono>

#include <thread>

using namespace v8;

// Stays in scope the entire time the addon is loaded.

Persistent<Object> persist;

void mutate(Isolate * isolate) {

while (true) {

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(500));

// we need this to create a handle scope, since this

// function is NOT called by Node.js

v8::HandleScope handleScope(isolate);

Local<String> key = String::NewFromUtf8(isolate, "x");

Local<Object> target = Local<Object>::New(isolate, persist);

double current = target->ToObject()->Get(key)->NumberValue();

target->Set(key, Number::New(isolate, current + 42));

}

}

void Start(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

Isolate * isolate = args.GetIsolate();

persist.Reset(isolate, args[0]->ToObject());

// spawn a new worker thread to modify the target object

std::thread t(mutate, isolate);

t.detach();

}

void init(Local<Object> exports) {

NODE_SET_METHOD(exports, "start", Start);

}

NODE_MODULE(mutate, init)

Note - we’re not using libuv or any of the (best) common practice you’d normally see in an async addon; just ordinary C++ threads. Let’s update the JavaScript to print out obj each second so we can see the fabulous work our C++ thread is doing.

const addon = require('./build/Release/mutate');

var obj = { x: 0 };

addon.start(obj);

setInterval( () => {

console.log(obj)

}, 1000);

If you’ve tried this before, you know what’s coming next!

> node mutate.js

Segmentation fault: 11

Lovely. It turns out V8 doesn’t allow what we’re trying to do. Specifically, a single V8 instance (represented by an Isolate) can never be accessed by two threads. That is unless, of course, we use the built in V8 synchronization facilities in the form of v8::Locker. By using v8::Locker, we can prove to the V8 isolate that we are switching between threads - but that we never allow simultaneous access from multiple threads.

Understanding V8 Locker objects

Viewing V8 isolate as a shared resource, anyone familiar with thread synchronization can easily understand v8::Locker through the lens of a typical synchronization primitive in C++ - such as a mutex. The v8::Locker object is a lock, and we use RAII to use it. Specifically, the creation of a v8::Locker object (constructor) automatically blocks and waits until no other thread is within the isolate. Destruction of the v8::Locker (when it goes out of scope) automatically releases the lock - allowing other threads to enter.

We have two threads: (1) the Node.js (libuv) event loop and (2) the worker thread. Let’s first look at adding locking to the worker:

void mutate(Isolate * isolate) {

while (true) {

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(500));

std::cerr << "Worker thread trying to enter isolate" << std::endl;

v8::Locker locker(isolate);

isolate->Enter();

std::cerr << "Worker thread has entered isolate" << std::endl;

// we need this to create local handles, since this

// function is NOT called by Node.js

v8::HandleScope handleScope(isolate);

Local<String> key = String::NewFromUtf8(isolate, "x");

Local<Object> target = Local<Object>::New(isolate, persist);

double current = target->ToObject()->Get(key)->NumberValue();

target->Set(key, Number::New(isolate, current + 42));

// Note, the locker will go out of scope here, so the thread

// will leave the isolate (release the lock)

}

}

At this point, since we haven’t added locking anywhere else, you might think this would have very little effect if we run our program now. After all, there is seemingly no contention on the V8 lock, since the the worker is the only thread trying to lock it.

> node mutate.js

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 0 }

{ x: 0 }

^C

This is not what we see though… instead, we see that our worker thread never acquires the lock!. This implies our event loop thread owns the isolate. Diving into the Node.js source code, we can see this is correct!. Inside the StartNodeInstance method in src/node.cc (at time of this writing, around line 4096), a Locker object is created about 20 lines or so before beginning to process the main message pumping loop that drives every Node.js program.

// Excerpt from https://github.com/nodejs/node/blob/master/src/node.cc#L4096

static void StartNodeInstance(void* arg) {

...

{

Locker locker(isolate);

Isolate::Scope isolate_scope(isolate);

HandleScope handle_scope(isolate);

//... (lines removed for brevity...)

{

SealHandleScope seal(isolate);

bool more;

do {

v8::platform::PumpMessageLoop(default_platform, isolate);

more = uv_run(env->event_loop(), UV_RUN_ONCE);

if (more == false) {

v8::platform::PumpMessageLoop(default_platform, isolate);

EmitBeforeExit(env);

more = uv_loop_alive(env->event_loop());

if (uv_run(env->event_loop(), UV_RUN_NOWAIT) != 0)

more = true;

}

} while (more == true);

}

....

Node.js acquires the isolate lock before beginning the main event loop - and it never relinquishes it. This is where we might begin to realize our goal of accessing V8 data from a worker thread is impractical with Node.js. In other V8 programs, you might very well allow workflows like this, however Node.js specifically disallows multithreaded access by holding the isolate’s lock throughout the entire lifetime of your program.

What about Unlocker?

If you look at the V8 documentation, you will find a counterpart to Locker though - Unlocker. Similar to Locker, it uses an RAII pattern - whenever it is in scope you’ve effectively unlocked the isolate. Perhaps we could use this in the event loop thread to unlock the isolate…

// Remember - this is called in the event loop thread

void Start(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

Isolate * isolate = args.GetIsolate();

persist.Reset(isolate, args[0]->ToObject());

// spawn a new worker thread to modify the target object

std::thread t(mutate, isolate);

t.detach();

// This will allow the worker to enter...

isolate->Exit();

v8::Unlocker unlocker(isolate);

}

Running this ends in disaster though - segmentation fault as soon as Start returns - the worker thread never even gets a chance. This really should not have been a surprise. When Start returns, it’s relinquished the lock it had on V8 and actually exited the isolate - but this is the thread that actually runs our JavaScript - a clear conflict in logic! The seg fault is a result of Node.js calling into V8 (to return control back to JavaScript) after it’s exited the isolate. If we delay the return of Start, we can see that the worker thread is able to access V8 data.

void Start(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

...

isolate->Exit();

v8::Unlocker unlocker(isolate);

// as soon as we return, Node's going to access V8 which

// will crash the program. So we can stall...

while (1);

}

> node mutate.js

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

...

In theory, we could force JavaScript to call into the addon to periodically release the isolate to allow the worker thread to access it for a while.

void Start(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

Isolate * isolate = args.GetIsolate();

persist.Reset(isolate, args[0]->ToObject());

// spawn a new worker thread to modify the target object

std::thread t(mutate, isolate);

t.detach();

}

void LetWorkerWork(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value> &args) {

Isolate * isolate = args.GetIsolate();

{

isolate->Exit();

v8::Unlocker unlocker(isolate);

// let worker execute for 200 seconds

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::seconds(2));

}

//v8::Locker locker(isolate);

isolate->Enter();

}

And here’s the JavaScript, graciously calling LetWorkerWork.

const addon = require('./build/Release/mutate');

var obj = { x: 0 };

addon.start(obj);

setInterval( () => {

addon.let_worker_work();

console.log(obj)

}, 1000);

As you can see - this does work - we an access V8 data from a worker thread while the event loop is asleep, with an Unlocker in scope.

> node mutate.js

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

{ x: 84 }

Worker thread has entered isolate

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

{ x: 168 }

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

Worker thread trying to enter isolate

Worker thread has entered isolate

{ x: 252 }

...

While this makes for a nice thought experiment - it’s not practical. The purpose of this entire exercise is to allow a worker thread to asynchronously work with JavaScript data. Further, we wanted to do this without copying lots of data which would slow down (block) the event loop thread. Keeping those goals in mind, the unlocker approach fails miserably - the worker thread can only access V8 data when the event loop is sleeping!

Why typical async addons work

If you’ve written async addons in C++ already, you surely have used Persistent handles to callbacks. You’ve gone through the trouble of copying input data into plain old C++ variables, used libuv or Nan’s wrappers to queue up a work object to be processed in a worker thread, and then copied the data back to V8 handles and invoked a callback. If you haven’t done this - read this now, so you understand what I’m talking about.

It’s a complicated workflow - but hopefully the above discussion highlights why its so important. Callback functions (passed in as arguments to our addon when it’s invoked) must be held in Persistent handles, since we must access them when our work thread is completed (and well after the initial C++ function returns to JavaScript). Note however that we never invoke that callback from the worker thread. We invoke the callback (accessing the Persistent handle) when our C++ “completion” function (in Nan, our HandleOKCallback) is called by libuv - in the event loop thread.

Once you understand the threading rules, I think the elegance of the typical async solution pattern becomes a lot more clear.

Workarounds and Compromises

Our premise was that we could have a C++ addon that used data from JavaScript as input. Since we now know making a copy is necessary - we come back to the issue of copying a lot of data. If you find yourself in this situation, there may be some very simple ways to mitigate the problem.

First - does your input data really need to originate from JavaScript? If your addon is using a lot of data as input, where is that data actually coming from?

Is it coming from a database? If so, then retrieve it in C++ - not JavaScript!

Is it coming from a file (or an upload)? If so, can you avoid reading it into JavaScript variables and just pass the filename/location into C++?

If your data doesn’t sit somewhere already, and JavaScript code is actually building it up incrementally over time (before asking a C++ addon to use it), then another option would be to store the data in the C++ addon directly (as plain old C++ variables). As you build data, instead of creating JavaScript arrays/objects - make calls into the C++ addon to copy data (incrementally) into a C++ data structure that will remain in scope. Even better, use ObjectWrap techniques to allow JavaScript to load data into a C++ object wrapped in V8 accessors. JavaScript can work with C++ addon result data like this too - the worker thread can build up a C++ data structure wrapped in V8 accessors and your JavaScript can pull (copy) data from the structure when ever it needs to. While this approach does not avoid copying data, when used correctly it can avoid holding two copies of large input/output data - it only requires JavaScript to have copies of the parts of the shared data structure it needs “at the moment”. Finally, we can avoid copying data entirely if we are willing to to store our data entirely in buffers, which is explained in detail here.

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has made it a little more clear why multi-threaded, asynchronous addons written for Node.js should follow the types of design patterns outlined here and here. In summary, asynchronous addons must always access V8 storage cells from the Node.js event loop thread, and not their worker threads. This unfortunately means you’ll need to copy data out of V8 to work on it in your worker threads, and then copy result data back when the job is complete.

In most situations, it’s not a big deal - but sometimes when input/output data is large, you’ll be tempted to avoid copying lots of data when invoking your addon. As I’ve explained above, there are workarounds that limit this problem - especially using V8 accessors and ObjectWrap techniques. If you are interested in seeing more on those topics, stay tuned by signing up for newsletter - I plan to post an article soon on these subjects. While your at it, you might be interested in my ebook that covers all things Node/C++ as well. You can buy it here